Stardew Valley, Hauntology, Belonging

This essay is a bit of a rambling mess in which I’m trying to work out thoughts around belonging, fragmented arts communities, and the game Stardew Valley. It’s not well-realised and is probably the beginnings of something more coherent and cohesive. I had originally planned, and started writing, a progress blog for my piece orr net, but it never really got anywhere. So this is also a bit of a substitution for that.

Stardew Valley is a well-known, and as far as I can tell, pretty well-liked game available on most platforms. It’s a farm/life sim and, despite having attempted it multiple times before with no success and minimal interest, playing at at this point in my life has resulted in a moderate level of addiction. I think about my farm a lot, I think about what I’m going to do next in the game, what I’m saving up for, who I talked to that day, and so on. This is obviously a distraction from more important things, but it’s not an unwelcome one. The game, whether by design or not, is provoking a strangely profound nostalgia, aided, perhaps, by finishing Crying in H Mart by Michelle Zauner this week. Not a nostalgia for the past (although that too), but for a kind of lost future. Maybe I’m just seeing everything through the lens of Fisher/Derrida’s hauntology, but Stardew Valley’s entire concept seems hauntological, from the perspective of the player, in a way that I don’t generally experience in games. It taps in to the very real desire to leave the grind of the city and build something physical (a farm) sustainably from a non-fucked land through labour, while contributing meaningfully to, and engaging in a small and generally supportive community. It’s obviously a complete fantasy, but it’s a fantasy that in some ways is not too far away from what could be possible, or at least, could have been possible. A few different decisions in life – mine and my parents’ – could have led me to something in the vague realm of what this game offers. I spent the first six years of my life in a very rural area, which could have had the potential for this kind of Stardew Valley situation. As a comparison though, living rurally like that, there is no way to reasonably walk to visit your neighbours; the sense of community (particularly community aligned with your own values) is virtually non-existant, and; that life is hard. So a lost future, yes, but also very obviously fantasy.

This community component of the game is what is most apparently hauntological for me. While people are friendly-enough to the player when they join the township, most NPCs are at best civilly indifferent. As the game progresses and you contribute more and more to the community, through labour, the townsfolk warm to you (mostly), regardless of whether you bribe them with presents or not. This serves double purpose in the context of this essay; first, it reinforces the neo-liberal narrative that hard work (labour) is rewarded, in this case through social inclusion, and second, that communities of people are not in fact highly fragmented in the years since the game was produced and released (2016) – a moment of hauntology. It is perhaps naïve of me, but the corporatisation (and filtering) that the internet has gone through, really since test cases such as AOL, but ultimately through platform capitalism in the form of Google/Alphabet, Facebook/Meta, Amazon, and so on has dramatically reduced the potential for physically fragmented communities to convene virtually. This was the promise of the internet for those who used it in the 1990s and early 2000s, especially those who found connection and community in these virtual spaces. Another lost future, though manifesting in a wildly different, corporately-controlled way.

Hauntology is a concept that I’ve been thinking about for a few years now, since I came across Mark Fisher’s use of it in relation to Burial and other artists. The concept of lost futures (which is a bit different to Derrida’s original conceptualisation of it), that we’re in a kind of hauntological loop at this point in time; that we have lost the ability to imagine a future (and specifically a future free of capitalism, but I would say almost any future), and so we look to the past for their imaginings. In this way our nostalgia for the past creates a kind of nostalgic future that will never happen, that future becomes lost and we become trapped in this hauntological loop. I think Stardew Valley taps into this in a similar, though less poignant way to that of some Studio Ghibli films. Nostalgia for a better, simpler past, becomes an imagining for a future that we can never achieve. The fantasy of Stardew Valley. This perspective on the game got me thinking about the arts scene here in Melbourne, and my connection with/to it. It is easy to remember a time when I felt more active in the scene, more engaged, and that there were events on the calendar for the year that marked a kind of significant moment, such as the Bendigo International Festival of Exploratory Music, and my co-creation, Tilde New Music Festival. There was also quite a lot of other activities at least semi-regularly; there was a kind of perceptual buzz of activity, non-traditional concert music venues (such as art galleries) were performing some music from here and abroad. It was by comparison easy to feel connected. But underneath all of that, I perceived a kind of factionalism that still exists, as far as I can tell, today, amplified by the end of things like BIFEM, Tilde, and of course by the two years of on-again-off-again lockdowns.1 This factionalism is an antithesis of sorts to the cohesive community presented in Stardew Valley – a fragmented artistic community. I’ve written before about how the Australian funding model(s) make enemies of us all, producing an environment of antagonism, not solidarity. I believe this is at least a part of the factionalism, but there is ideology as well. Free improvisation, jazz, art music (but if it’s too European it could “just be improvised”2 and so the practitioners tend to end up in the free improvisation team(s)), noise music, the adjacent visual arts, dance, and theatre. And through my own choices, I don’t really belong in or to any of these factions anymore. The thin threads of cohesion that I remember existing seem to no longer exist, and I find myself in a hauntological loop of trying to imagine a future (I can’t) and so falling into the trap of nostalgia; looking to the past to imagine a future and realising that perhaps my memory of the past is heavily biased.

This factionalism is natural as people gravitate towards both the means of production available to them (these are very limited in Australia as a whole, for non-commercial music and increasingly for commercial music also), and while I think it would be a good thing to reduce this fragmentation and increase solidarity between artists, I do understand, given the economic circumstances and perceived aesthetic “territories”, that it is a natural state. I don’t know if it’s the years of burnout and withdrawal from these various scenes that is the cause, but I don’t really feel a sense of belonging to these worlds – any of them. Lacking the economic (time, money, energy, geographic location) means to engage with almost everything all the time leads to a state of inaccessibility and fundamentally alienation. I am perhaps the only person who feels this way, but my suspicion is that for the most part, the corporatisation and economic pressures of the last few years have eroded the capacity of people to be truly engaged, coupled with institutional withdrawal (such as universities becoming very insular) reducing the available opportunities, and shifting political ideals, lead to a fragmentation of belonging. Stardew Valley, on the other hand, offers an escape from this – a sense of belonging and ease that is not really possible in the world. When one reads about the various histories of the arts in Melbourne (and in Sydney, New York City, London, Paris; places that have been considered “hubs” of artistic activity), one is necessarily reading a very biased and unnatural view of things, and one is reading of tremendous social and political exclusion (of women, disabled people, people of colour, and so on) though it is never written as such. Nonetheless, it is striking as to the sense of shared goals, of an imagined future that, in some ways, came to pass, and which now seems to be lost.

As mentioned above, I’ve been trying to figure out how to capture this loss of belonging, loss of the future, in my creative work without it being highly contrived and without resorting too much to forced narrative/extramusical context (i.e. a leitmotif representing a lost future). It’s been quite difficult, because there is a kind of contradiction – how does one compose/create a sense of nostalgia or a lost future or whatever? Experiencing Stardew Valley, along with talking to a friend about some of these things, has got me to the point of realising that my interest in “glitch” art (not just the ‘90s/‘00s electronic music aesthetics) is a fruitful area to explore this. A glitch, for example, a CD player skipping part of the data stream due to a scratch, or an image file becoming corrupted, acts as a kind of sudden, unexpected interruption to a flow of information; in a sense, it disrupts the future. If we think of our perception of music as the transformation of sound in time, then we get a fascinating and moving interplay between memory and imagination; we imagine a future based on the past. A glitch – an interruption of some kind – to that flow of processing, therefore, has the potential to break that interplay; to functionally “lose” a future that was imagined from the past. There are many ways in which this could be realised musically; we hear it in the striving/risk of really great jazz-based improvisation; in the hyper complexity of performing certain music that originated around the middle of the 20th century; in the difficulty and tension of durational performance (such as Feldman), and of course, in much electronic music where the systems that are used to create it are inherently unstable. Maybe it’s self-aggrandising, but I feel as though there is something in this that reflects the fragmentation of society as a whole, and certainly my sense of fragmentation of the present. It’s not a dehierarchicalisation, per se, but a complete fragmentation. Continuously lost futures, continuous nostalgia, and a lack of belonging. Where Stardew Valley (and similarly “cosy” games, stories, etc.) offer a balm to this feeling; moments of escapism, I hope that art and artistic activity can reflect this state and thus help to heal it. I have no idea how that might work, but I hope that it does. For my part, I know I need to participate again, to engage, and to find some of that connection that I’m sure is there, and of course to produce this art that I imagine.

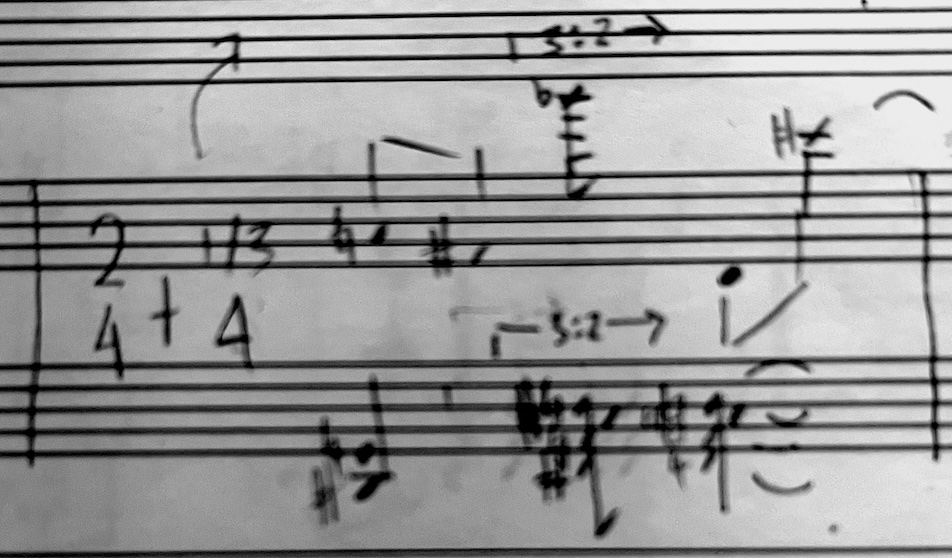

I’ve begun to consciously explore this in my piece orr net, which is nearing first draft completion. It’s for solo piano, and mines my past (and the musical past) as a source of material in the form of Ornette Coleman’s Lonely Woman from The Shape of Jazz to Come. Transfiguring the music into a new form; bringing the past to the present, and within the musical morphology, playing with moments of discontinuity. For example, this measure containing two quarter-notes and a single note from a set of three triplet-eighth notes. The implication with this gesture is that the extremely temporary adjustment to perceived speed of information could cause a jolt to expectation. A rapid adjustment to imagined futures that is rapidly subverted again. This is in the context of continuous changes to time perception throughout the piece, that I hope will play upon these lost futures. This isn’t anything particularly new; indeed, harmony has long been the dominant musical parameter with which expectation is subverted, and I suspect that many composers have been playing with the concept in other parameters, such as electronic glitch music (and more widely, art), the temporal manipulation in “new complexity”, the timbral work that came from the spectral composers, the sudden gestural interruption often found in free improvisation, and so on. These gestures that disrupt the flow of the surface of the music.

I’d be keen to know of other people’s approaches, of their feelings of belonging within the arts here (or elsewhere), and if anybody were willing to share strategies to come back from massive withdrawal, I’d be keen to hear about that, too.

Notes

I think the lockdowns were both important from a public health perspective, and proportional, and indeed, abandoned too soon. I also think that while they definitely had negative impacts for people, it showed some pretty severe cracks in the economic system that we exist in, and that seems to have largely been “forgotten” now. ↩︎

This has been an attitude that I’ve encountered many, many times in the past, and it talks to a surface-level comprehension of a considerable body of music. This is often heard in other artforms as well, particularly around modern art movements. The refrain goes “my kid could have made that”, with the adult-practitioner version being “just improvise it”. This is obviously a fallacy, but I suspect that at least part of the factionalism that I’m describing here is this attitude in a logical conclusion. It is easy to be dismissive of art that we dislike, but it takes bravery to admit to simply disliking it, without making fallacious justifications for its invalidity. ↩︎