Arbitrary Complexity Thresholds

The Arbitrary Dismissal of Complexity

If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then sixteen. Then thirty-two. Eventually one discovers that it is not boring at all.

–John Cage, from Silence: Lectures and Writings (ed. Wesleyan University Press, 2010)

I wrote this zine earlier in 2024 as a self-writing exercise to think-through something that has bothered me for a long time – the generalised opposition to so-called ‘complex music’. To kind of blurt it out before formalising the thoughts further, and elaborating. The goal of this essay is to examine parts of the zine and expand upon them, reflect on them, and bring some perspective provided by time.

The issue that I’m feeling here comes from one of isolation and alienation and anger as a result. In this case, later in my life, it comes to a kind of specific-enough point to highlight something a bit more universal – that the issue is my own, rather than externalised. I think my first instance of this kind of alienation was wondering why the bulk of people that I encountered (including many people who are clearly interested in music, often being musicians themselves) did not enjoy listening to what could have been contextually considered “virtuoso” playing, often calling it “unmusical” or “doesn’t feel good” or equivalent. This could have been Les Claypool in Primus, or Victor Wooten in The Flecktones, or Joe Satriani playing… Joe Satriani. I experienced many people in my life with this kind of attitude. The next instance would be when I got into jazz (and consequently, taking solos), and the same basic objections come up, but this time it relates to a kind of complexity stemming from harmony, mainly, I think. To be clear, I’m not talking about my own playing, but rather sharing my excitement with people – friends, mostly, but sometimes colleagues – and being met with this response of “it clearly takes a lot of skill… but it’s not very musical” or similar sentiments. Later, when I started studying composition at a university, I had my first experience of this when my lecturer got us to listen to a piece by Helmut Lachenmann, and my response was “this is not music!”, however I got past that quite quickly and came to understand more about the context and the wonderful musicality in the work, and so on. It was compelling, even in my initial rejection, and it was compelling because of the discourse it generated in my naïve self and classmates. This eventually led to a bewilderment with the art music world, particularly in Australia, that does not prioritise new music (which is in contradiction to every other field of music I’ve ever worked in, and this is still something that I find bewildering, but that’s another essay and zine). This bewilderment (and, admittedly, often anger) would lead to the co-creation with Alice Bennett of the Tilde New Music Festival (and eventually Academy that ran until 2019 and is currently on an indefinite break. But it didn’t really provide a balm to what I was feeling, and admittedly still do. This essay is not about that, though it is adjacent, it’s about “complexity” and pondering the seemingly arbitrary limits and boundaries that people (and I include myself in this, especially in retrospect) put on their tolerance for “complexity”.

I didn’t do this in the zine, but I hypothesise now that there is an economic factor at play, that there is a threshold (in each individual based on their various cultural/social experience and context) past which economic rationalism (or instrumental reason) as a default kicks in, meaning that it doesn’t make sense to them as entertainment1 so the brain defaults to a position of economic context, which also doesn’t make sense because “who would pay money for this?” or “my five-year-old could do this!” or “I could just improvise this.” Basically: what is the point of this? And arguably, this same line of thinking absolutely applies to the new music phenomena above. If there is no obvious teleology to the thing to the person, then it seems to default to a position of economic worthlessness. This phenomena is not restricted to complex music; I have been in places and talked to people who share similar views to much contemporary visual art, theatre, and dance – I’m sure practitioners in these fields will have heard similarly disparaging comments as those above. My own trajectory in music has been one of increasing complexity, from starting out playing bass (and guitar) in a pop/rock context, moving to progressive rock/metal, then fusion/jazz, jazz, then to free improvisation, and composition and particularly 20th and 21st century new music (neuemusik) stemming from modernism and then high modernism and all the resulting aesthetic diversity. It may be arguable that this comes from increasing “learning” (through practice and education), but I think it’s more simple to to think about it as a desire in my creative practice to somehow transmute and reflect the kind of complexity that I experience and observe in my life. By way of example, the complex interactions of watching the various ’layers’ of a cityscape pass at different rates relative to the viewer whilst travelling in to a city on a train and looking out the window, or the interplay and dynamic structure of the human relationships I am in and which surround that in an ever-expanding network with each subnetwork of relationships being made of tensions, imaginable as lines of force connecting people in a vastly complex web that probably visually reflects neurons, or the complexity of observing the subtle and slow changes of plants and animal behaviours over the course of a year or longer time cycles. These are all perceptual concepts that feed directly into my work in music for the past fifteen or years or so, but my thinking around it is becoming clearer.

But “complexity” is all too often used, in certain musical (musicological) circles at least, as a comparative term, as something whose magnitude in a given context may be measured with what passes (none too convincingly) for scientific precision. (And, by extension, commodified and purchased by the pound.) This seems to me no more than a symptom of the kind of fear of perception which takes refuge in contorted quasi-rationalisations when faced with the potential perturbation of a musical experience.

– Richard Barrett

(see footnote2)

I understand that not all art/music resonates with everybody; admittedly I used to get frustrated at this in the “but this is so wonderful!” but I get it; not everything resonates. I don’t know that it’s a matter of taste, but everybody’s physiology is so input to that physiology is going to resonate differently. What I find interesting, and what is the point of this essay (and the zine that this is elaborating on) is that the boundaries of acceptable ‘complexity’ seem really quite arbitrary, or inherent complexity in various musics seem to be completely ignored or overlooked or unacknowledged. What follows is not, by any means, an attempt at classification by the category of relative ‘complexity’, rather to show that much that we take for granted as being ‘simple and accessible’ by no means not-complex, and that thinking about this might (I hope, at least) open one up to the possibility of a richness of experience that they may be missing out on. I would also add that despite the fact that I love ‘complex’ music and art, there are works that are for me vastly more demanding to listen to, and I don’t always want to put that demand on myself (or have it put on me). We live complex lives and sometimes perceived complexity can be a balm for that, and other times not.

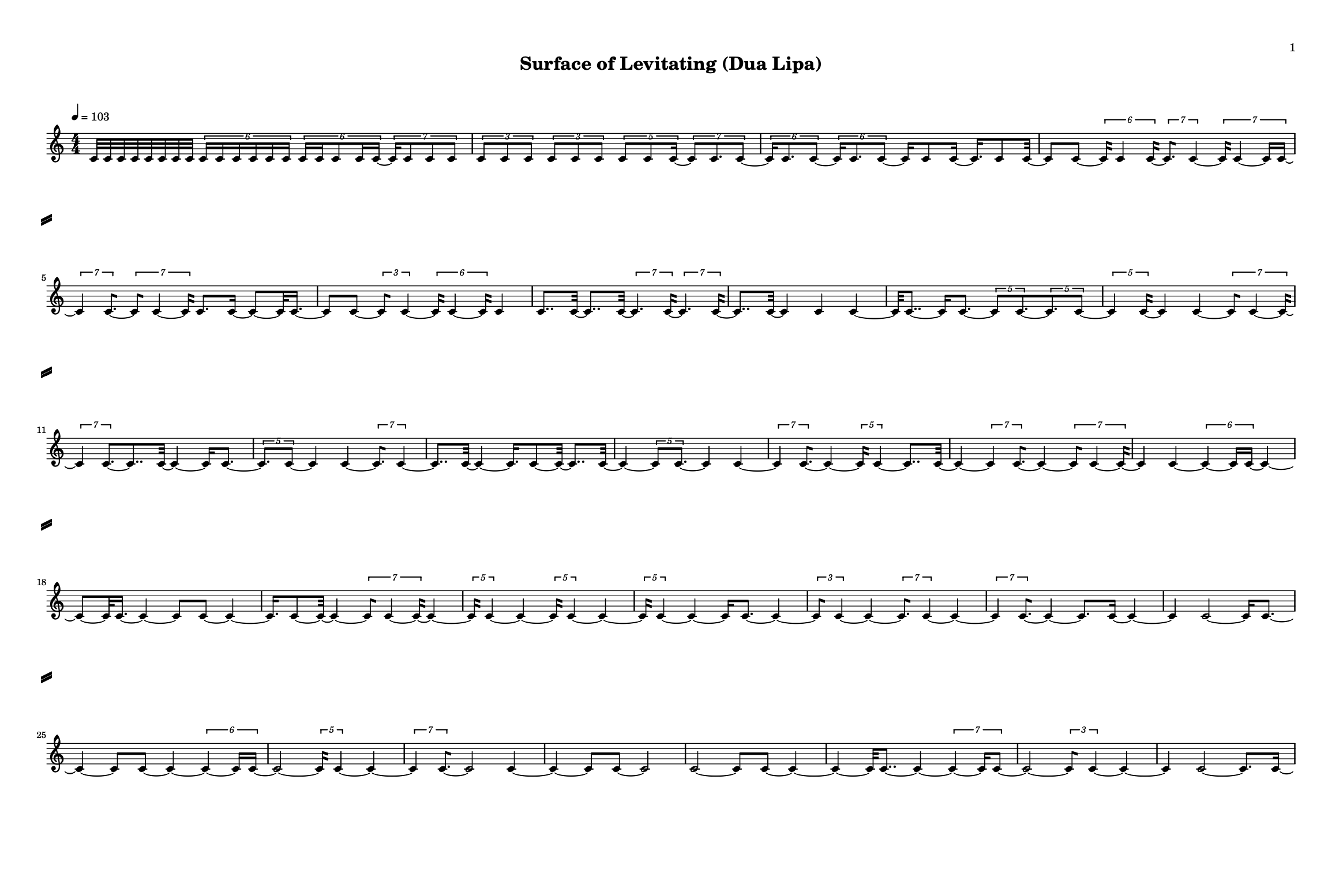

The following example is roughly the first 1'36" of Dua Lipa’s Levitating (ft. DaBaby), and is possibly a somewhat misleading analysis that I wouldn’t use for any serious musicological research, but it does demonstrate somewhat my point of the weird arbitrariness of ‘complexity’.

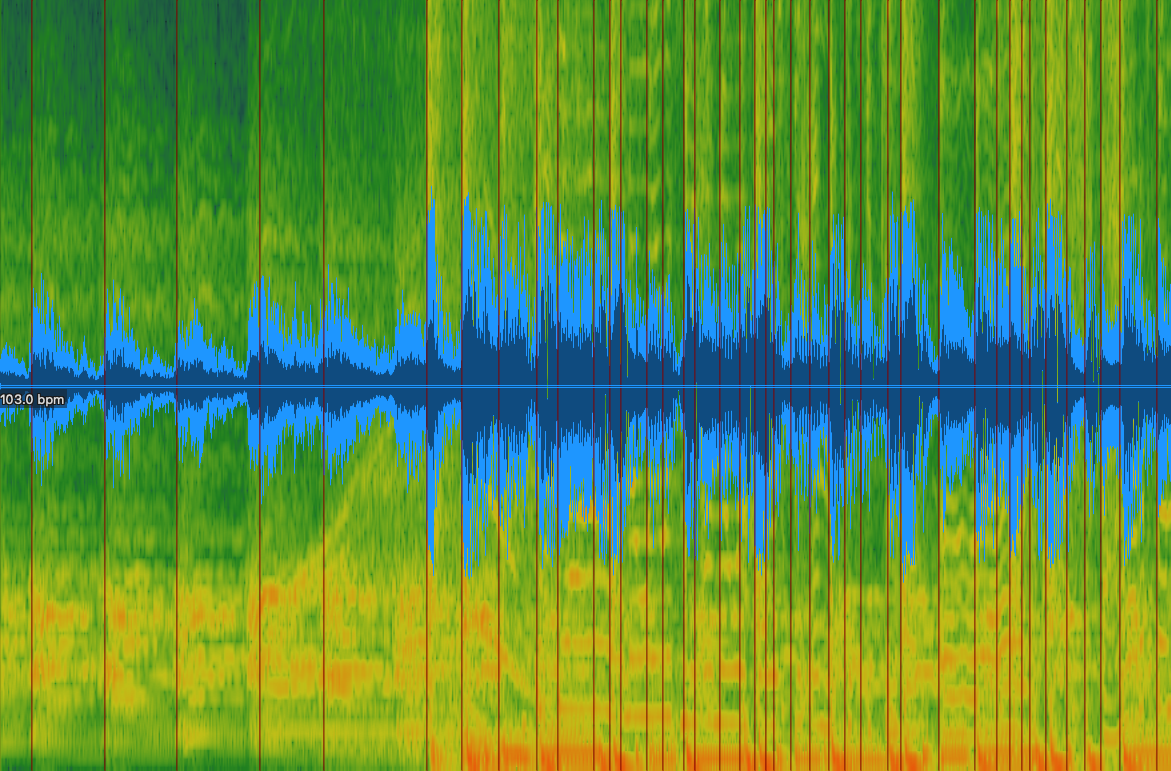

The following text shows the first 17 onset points in time taken by analysing the wave form of the song. This represents every ‘perceptual’ onset at the topmost surface-level of the song, meaning that every obvious percussive hit, vocal utterance, etc. is tracked (to whatever threshold the analyser was set). A number of these onsets are very small in their increment, being in the order of 130ms or less, in some cases. Not to the level of microsound3, by any stretch, but still, quite short. It could be argued I think that this represents a kind of approach to ‘swing’. What is clear though is that these are absolutely not perfectly equidistant. This also does not factor in things like delay at the start of the file that was analysed or anything like that.

|0.255291667|

|0.835500000|

|1.415708333|

|2.077145833|

|2.587729167|

|3.411625000|

|3.690125000|

|3.991833333|

|4.293541667|

|4.456000000|

|4.746104167|

|4.873750000|

|4.966583333|

|5.175458333|

|5.303104167|

|5.465562500|

|5.558395833|

I then wanted to see how that would quantise into notation, and used OpenMusic to do so. Now looking at the onsets I’m not convinced that this is accurate, but quantisation always lacks nuance.

This shows an interesting potential perceptual surface to the music based purely on its rhythmic values, and it is very clearly complex, with microfluctuations around the beat (indicating a type of written-out swing). Even if this represents some level of the surface of the song, I think this shows what I’m getting at quite clearly.

Finally, the image below shows the original analysis that this was derived from (including the tempo). So while I don’t think there is a strong correlation between this and the notation, what this does show is that at the surface, there is a significant amount of rhythmic variation indicating onset variability and non equidistant rhythmic interplay at the level of the surface.

While this analysis is pretty weak, it does encourage a deeper examination of how we seemingly apply an arbitrary threshold to what we perceive in music, and we can seemingly tolerate certain levels of complexity in a given context (say, swung rhythm and microtiming in this Dua Lipa song) that we find more difficult when abstracted further at subsurface levels.

What this suggests, to me at least, is that when it comes to musical complexity, perhaps we should collectively be less instantly dismissive of music that makes a higher demand of us than we may be used to, or than we may expect, and that we should interrogate our relationship to all art based on the economic contexts in which we find ourselves. It should give us pause to consider how we talk about music, about what we “like” and what we “dislike” (or more polarisingly, what we “hate”), and that perhaps there is room for our engagement and enjoyment of art to be more than just immediately/intuitively “love” or “hate”, and a more nuanced, more complex discourse around art will help everybody’s appreciation of it. Or, at the very least, prompt a deeper listening to things we consider “simple” and to interrogate our conceptions of what makes something “simple” in the first place. For me at least, I just don’t think music is simple. Even “simple” music is not simple. The above quasi-analysis doesn’t even factor in any layers of complexity induced by the lyrics and semantic or poetic meaning to them. These dimensions provide further depth, even in what would, I think, be dismissively called a “simple” pop song. Below are the same examples, less the one examined above, from the zine, of where I feel obvious complexity is overlooked in the music.

- Microsound/granular textures in FKA Twigs

- Harmony, rhythm, lyrics in Björk

- Concept and harmony in The Beatles

- Timbre and narrative in Nick Cave

- Harmony and rhythm in bebop

And to close, here are some links to video/audio with quite wonderful “complexity”.

- Liza Lim’s Invisibility - wonderfully sonorous and fascinating use of time.

- FKA Twigs’ album MAGDALENE, and specifically the title song

- Radiohead from OK Computer on, but a good example is Bloom from King of Limbs that includes a lot of complex layers of rhythm and interesting harmony.

- Joni Mitchell’s narrative structures, such as the interlocking tension between career and a lover on the album Blue, and the music itself is very harmonically rich.

- Richard Barrett

- Evan Johnson

- Helmut Lachenmann (and Guero, the piece to which I reacted when I was younger)

- Ash Fure

- Jennifer Walshe

By no means exhaustive, but hopefully anybody reading this can get a little further into the rabbit hole and perhaps make some connections between musics where they did not have them before.

Notes

This is its own thing too, but in short: music appears to inhabit a liminal state where, on the one hand it is considered primarily as entertainment (terms like “entertainment industry”, “music industry” etc. are telling) and, on the other hand, it is considered primarily as art. Musicians will (generally) consider what they do as a form of art that may happen to be entertaining, and beyond that it’s kind of hard to say, and this warrant’s deeper reflection and information gathering. ↩︎

Generally considered to be be less than about 50ms. ↩︎