Through-lines from Finnissy's notion of transcription to my current and past work

This short essay will form one of several in a series that form my investigation into composer Michael Finnissy’s notion of transcription as a form of music-making. An idea that has become very attractive to me, and, I suspect, if I were to undertake another PhD, or even a masters, in composition, it would form the basis of the through-line of music creation along with a through-line of (some) existing work.

Finnissy, in this interview describes transcription as a “something that you are writing through” and “as you’re writing through you’re thinking along the way, as you go,” in contrast to arrangement, which he says presupposes that “you haven’t done very much to the shape [of the piece] to alter it”. The Apple dictionary defines transcribe as “put (thoughts, speech, or data) into written or printed form” or to “arrange”, as in the case of music. Neither are particularly useful. I remember coming across a definition that was something like: “to copy from one medium to another” or something like that, which is somewhat alluded to in the dictionary. The online Merriam-Webster dictionary does include this useful little definition “to paraphrase or summarise in writing”. While the very first definition provides a lot of insight into the specifics of what Finnissy says, this short essay is an attempt to further grasp, and think through what I think Finnissy means by transcription, and how it might apply to current and past work. It could be said to be a transcription, of sorts, of that short segment of interview. Finnissy does go into more detail around transcription, including some reference texts that I have not yet addressed, however, what follows is a kind of initial thinking-through of the idea from that one specific line.

Understanding transcription

There are some words within the same general area that may be helpful here. They include:

- Transcode: convert (language or information) from one form of coded representation to another;

- Transduce: convert variations in (a physical quantity) into an electrical signal, or vice versa;

- Transform: make a marked change in the form, nature, or appearance of;

- Transfuse: cause (something or someone) to be permeated or infused by something;

- Translate: move from one place or condition to another.

And so on.

These definitions give enough clues to, I think, what Finnissy is getting at when he talks about writing through, thinking through, along the way as the process of transcription. First, because he is talking about music, specifically, the process of transcoding seems relevant; music could be perceived of as a form of coded representation, especially when dealing with music notation. So even in traditional notions of transcription, for example: using aural skills to transcribe something heard into notation, could be loosely conceived of as a form of transcoding; of converting information from one form of coded representation (sound waves in a medium) to another (notation). This also relates loosely to transduction, but only loosely; variations in a physical quantity.

Moving on to transform, which taken as the definition given above, describes quite well the result of Finnissy’s transcription process: something (a piece of music) that is markedly changed in the form or nature. In music composition of course transformation is a core part of the development of musical ideas, so actively transforming something through transcription is an interesting idea, particularly when combined with transfusion. Taking these two words together clarifies the thinking or writing-through process, meaning, the act of transcription imbues the resulting work (a transformation) with the process of thinking. That the character, aesthetic sense, musical technique, and all manner of other things will permeate the resulting music transcription.

The last on my list, translate, is interesting because like transcribe itself, it acts somewhat as a meta-term for these other concepts, encapsulating transfusion and transformation, and transcoding, where the person doing the transcription is translating what is heard or read, imbuing it with their experience, technique, personality, aesthetic sense, and so on, and thus transforming it, changing it, and moving it from one state to another.

I put forward this definition of transcription as I think Finnissy means it, which is not the commonly understood use in the world of music as described above, but does encapsulate it.

Something: a musical object.

That you are writing through: writing music through this object. That is, writing something new as if dragging it through the source object, imbuing the resulting object’s state with the character of the source object, thus transforming the state of the source object.

You’re thinking along the way, as you go: thinking, transforming, and applying your knowledge, aesthetic sense, and experience, to translate the source material into a new state, but doing so in response to the moment-by-moment translations of the source material.

As an interesting tangential note, this definition has a lot in common with improvisation, which Finnissy is involved in. In particular it suggests to me the process of real-time response to input (physical or mental) in improvisation, where an improviser responds to the environment, to music cues from other players, to prompts, seeds, or any number of musical strategies. This is something to be returned to in another essay.

Examples from my work

In this section I want to try to connect these ideas across two compositions, one current and one in the past. At the time I was unaware of Finnissy’s music except as being loosely affiliated with a certain aesthetic (’new complexity,’ which, after listening to a lot of his music, really is an inappropriate term. I will write something about that another time.) This happened for me somewhat with spectral music and Stockhausen’s formula composition, and the works that I will look at in this section do draw somewhat on those histories, too. However, I think the line from Finnissy is definitely present as well.

silver as catalyst in organic reactions (2016)

In 2014 I was composer in residence at the Bio21 Laboratory - part of the University of Melbourne. This residency was to develop music in collaboration (of sorts) with a scientist within the institute, and in this case I worked with Arthur Zavras, a chemist who worked on mass spectrometry. Given my interest in spectral music, the use of spectral data from somewhere else was a wonderful alignment of interest. The above-named piece (hereby known as silver)1 formed part of by doctoral degree in sound design2 and is discussed there in relation to spectral music and techniques. Relevant to this discussion on transcription is the techniques used to transcribe the audio generated by sonifying the mass spectrometry data using Open Music.

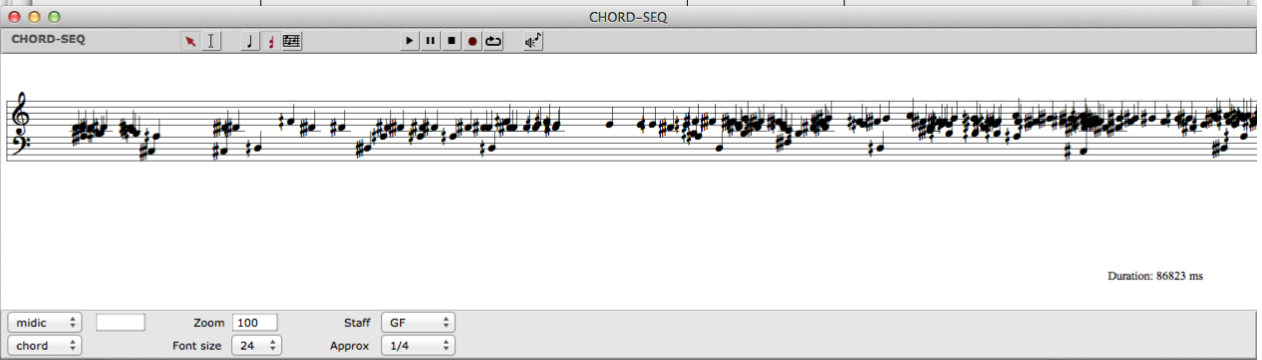

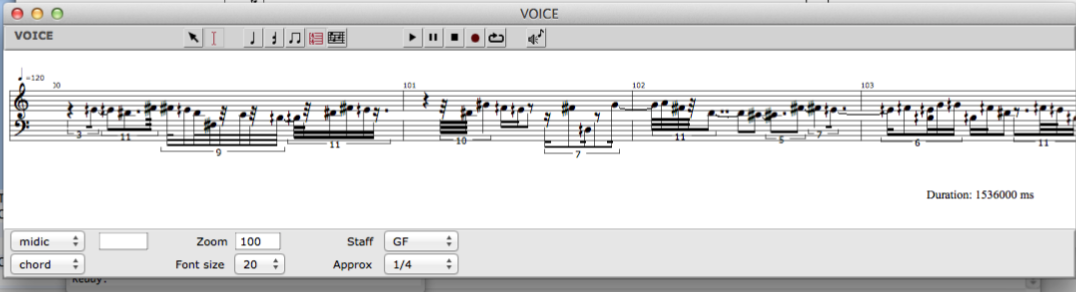

This first image shows the pitch material and proximity-duration scheme of a portion of the resulting music notation.

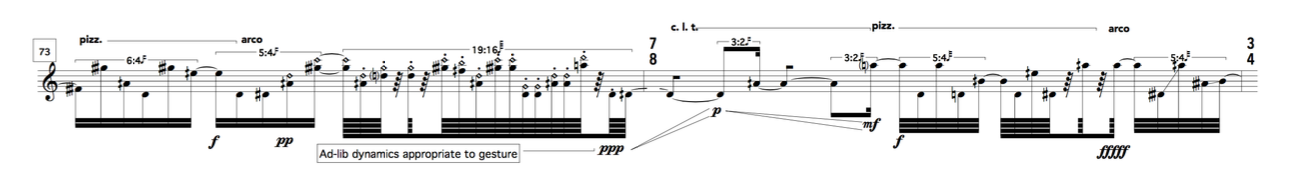

This is then interpreted, quantised, and then interpreted again, as demonstrated in the image below (a final set of phrases). This process very much resonates with the idea of transcription: taking something (source) and writing through it, resulting in something new that is not obviously related to the source material. If one were to compare the source audio for silver, with the resulting piece, I do not think anybody would reasonably consider these to be drawn from the same material, unless they have exceptionally good aural skills for vertically quantised pitch/frequency relationships over time.

Yet to be titled solo cello piece (2022)

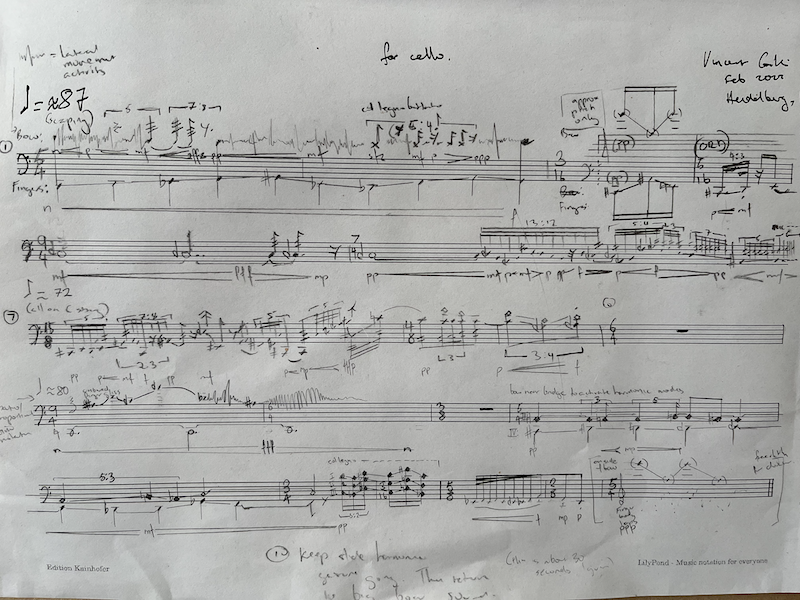

I have been slowly working on the first draft of a piece for solo cello that is based on an electroacoustic improvisation I recorded earlier this year. This really began with the interest in Finnissy, and his transcriptions, and is the motivation for this essay: to think through and document my initial investigations.

This piece differs substantially from silver, primarily because the transcription process is purely aural3 rather than mediated through computer-assisted techniques with Open Music. The source material is simply listened to actively, and I’ve been “thinking through” the piece. What is interesting about this is that I’m not attempting to transcribe it accurately, but rather capture the spirit of it. It’s like I’m dragging the new piece through the old piece, and trying to imbue some of the qualities on it. By writing-through the improvisation, the improvisation itself acts as repeated jumping-off points for tangential writing - the writing through process - akin to seeded improvisation4 but in reverse. Seeded composition?

So far, this mode of composition has been interesting and rewarding, familiar, but novel enough that it is hitting those reward centres in the brain. By focussing on moment-by-moment gestures within the recorded work, I am able to hear the landscape of the original piece, and imagine maybe an adjacent landscape, in a way that standard transcription – for accuracy – simply does not achieve. The process of writing through, of translating, transcoding, or transfusing within the transcription, offers an insight into both the new composition and the source material that I never expected, and a creative mechanism that I think will yield a lot of work for a long time.

To conclude

Because the piece is not yet finished, it’s hard to reflect on how this act of transcription has applied to a full composition, but already I can see the potential of this as a working method, encapsulating earlier methods of organisation and composition with computer assistance and threading a line back to earlier, more intuitively generated music. In other interviews (and in related documentation about ’new complexity’) Finnissy discusses a relationship to complex landscapes and moving through them, which will be a topic for another essay, particularly as I begin to read Songlines by Margo Neale and Lynne Kelly, as I suspect there will be an unexpected connection there. Similarly, Finnissy relates his musical practice to that of photography or film, as much as, if not more than, to standard notions of musical practice, and refers to Susan Sontag’s On Photography, another on my immediate to-read list.

I think there are the beginnings of a line of thought here, connecting current work to earlier work. Indeed, I think the connections to earlier work are more prominent than I realise, but would prefer to treat each example of that as its own analysis and reflection, and where possible to dig up my own documentation from those pieces to see if my memory is at all accurate. I am excited to look at pursuing this method in in a dust storm of altruism, which I haven’t started yet, and should probably think of a name for this cello piece.

In closing, what initially struck me was how and why this differs from variation technique, but as Finnissy points out, this follows on from the operatic tradition of transcribing an opera for piano, and other such things. To me this differs from variation techniques, as there is no theme that is being varied, per se. Naturally, variation techniques may (and probably do) form part of the repertoire of ideas that may be explored in the transcription, but nonetheless, I see this as separate from transformation. Finnissy draws a comparison to portraiture in painting, where the final work may not look “anything like” the subject.

Giles, Vincent. Silver As Catalyst In Organic Reactions. Score. Melbourne. Accessed 25 April 2022. ↩︎

Giles, Vincent. “Microsound, spectra, and objectivity: tracing memetics in organised sound.” PhD diss., 2016. ↩︎

As a tangent for future me, this also suggests a synergy of sorts with Pauline Oliveros’ deep listening practices, particularly “hearing” vs “listening”. I will return to that in another essay. ↩︎

See this description by Richard Barrett for more details. ↩︎